The Cabo de Gata area was formed when the African and European tectonic plates collided millions of years ago, and subsequent violent volcanic activity under the sea.

The result is an extraordinary landscape, which in places looks prehistoric.

Hills unravel along the coast, pitted like Swiss cheeses. Hidden coves with sparkling volcanic sand lie between them.

Starved of rain in summer, it can look barren and desert-like. In spring and autumn it is transformed; if it rains. Green grasses, red poppies, yellow, pink and white wildflowers bring colour and life.

Due to its remote feel, locked away in the south-east corner of Spain in Almería province, it became a favourite hang-out for hippies and travellers from the 1960s onwards.

Since first visiting at the turn of the century, I have noticed that the white-washed fishing villages have become smarter, slightly gentrified even, as the secrets of the Cabo de Gata have been revealed to the wider world.

Despite the gradual replacement of hippies by the moneyed classes and international tourists, it is still a place where peace and tranquillity can be enjoyed out of season.

Turning the Cabo de Gata into a protected natural park in 1987 saved it from the worst excesses of the construction and tourism industries.

Poor road links and a lack of public transport also helped.

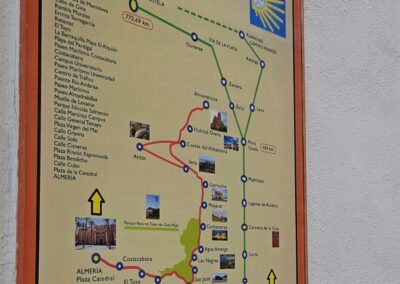

Buses do go to Mojácar, which is on a route from Murcia city and Almería. The service is operated by the company ALSA and tickets can be purchased via their website at www.alsa.es

So Mojácar is our starting point for a six-day hike which takes in some of the most secluded and inaccessible coves on the Mediterranean.

There is around 130 km of coast path, tracks and minor roads for the six stages, with approximately 2,400 metres of height gain on the route.

Some of the early stages are quite short and two days could be turned into one if time is short.

The GR-92 footpath is supposed to run along the Mediterranean coast of Spain, from the France border to Tarifa on the Strait of Gibraltar.

However, less than half of it has been waymarked. And Almería’s is one of the provincial governments which has failed to sign its coast path.

Despite their indolence, there is a waymarked route – but it’s not the GR-92.

Amazingly, even though this area is about as far away as you can get from Galicia on the Iberian Peninsula, there is a Camino de Santiago; it runs from Almería city to Mojácar before turning inland.

Named the Camino de Santiago del Levante-Sureste (and the Ruta del Argar), it uses white/blue waymarks and occasional signs.

As the coastline is hilly and fractured in places the waymarks are handy for orientation when the path heads inland to skirt obstacles.

The promoters of the Camino de Santiago del Levante-Sureste have done a good job of waymarking the route in most parts.

Watchtowers

There are more ancient watchtowers on this stretch of coast than I have seen on any other in Spain.

This historical and visual presence adds to the interest of hike, as well as providing markers on the horizon to make for.

Some were built by the Moors from the 12th century onwards and others were constructed after the Reconquest of Spain was completed in 1492 to protect the coast from incursions by Barbary pirates, who would loot and take inhabitants as slaves.

Most of the towers have information boards explaining when they were built and their historical context.

Fantastic fish

Another attraction is the fish on offer in the restaurants and bars.

If you set out in good time in the morning – and haven’t been distracted by swimming or sunbathing en route – then on most of the stages you will be able to indulge in a late lunch.

As well as the crowd pleasers such as bass, bream, tuna and swordfish, a whole host of other Mediterranean species appear on the menus.

Some of my favourites are ‘boquerones fritos’ (fried anchovies) and ‘sardinas’.

After walking next to the sea and viewing the fishing boats, it’s a fitting end to the day; indulging in the fruits of the sea.

Recent Comments