This vast mountain chain, that includes two national parks and stretches from coast to coast, is a haven for all sorts of wildlife, as well as providing pasture for livestock.

The high mountain areas near the passes and summits are home to the elusive chamois (rebeco in Spanish), a goat-antelope which only drops down to the pine forests during the winter. These graceful and incredibly agile animals are expert climbers and make themselves scarce very quickly when humans appear. The best way to see them is by keeping quiet, as with most wildlife. However, most walkers will only be aware of their presence when they hear falling stones in the distance, signalling that the chamois are in flight, scaling seemingly impossible rock faces.

Female chamois and their young live in herds of up to 100 individuals, although it is rare to see such large numbers. Adult males tend to spend most of the year on their own. It is possible to observe them from secluded positions in remote valleys; sometimes this occurs by accident while taking a quiet breather.

Another of the mountain dwellers which scurries away when walkers approach is the marmot (marmota in Spanish). A large ground squirrel, it is one of the star animals of the Pyrenees; one that people love to see and watch. They can be found right across the mountain chain. Walkers are usually alerted to their presence by the sound of the high-pitch whistle they use to communicate and warn each other of potential danger. Their burrows are usually found near mountain streams on the high pasturelands or grassy slopes. The best place to see them is at an altitude of roughly between 1,800 metres to 2,300 metres. A good way to do this is to settle down for lunch close to a stream, where burrows can seen. Keep quiet and more than likely the marmots will appear when they think you have gone.

One of the familiar poses of the marmot can be seen in the photograph; on hind legs to smell and scout the area. They hibernate during the freezing winters, so marmots are skinny in the spring but fatten up considerably by the autumn in preparation for their long sleep.

Even more elusive are the mountain foxes. I have only seen a couple in more than 20 years of walking in the Pyrenees. Fortunately, I had my camera in hand when one appeared at a height of around 1,800 metres on a cold, icy winter’s day. In the photo the fox seems slightly peeved that I manage to catch it on camera, and who can blame it.

Walkers can see griffon vultures (buitre leonardo in Spanish) when they are out in the mountains. Circling high overhead, riding the thermals, they are the most common large bird in the high Pyrenees. They are recognisable by their huge wingspan of 2.4–2.8 metres with black feathers on the outer section, and their white heads and necks.

The Vulture Conservation Foundation (VCF) explains that it is the most social of Europe’s four vulture species, feeding in groups and roosting and breeding in large colonies that can host hundreds of individuals. Following its decline in the continent over the 20th century, today it is Europe’s most populous vulture species, with approximately 35,000 breeding pairs, 25,000 of which are found on the Iberian Peninsula.

Eagles such as golden, booted and Bonnelli’s are seen much lower down the valleys around the villages and towns, where their hunting grounds are found.

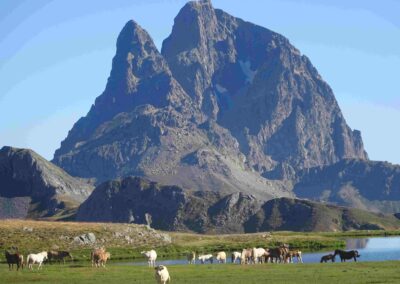

Regular visitors will know that it is difficult to walk in the Pyrenees in summer without seeing a cow. Amazingly these animals are comfortable at heights of up to around 2,400 metres – basically anywhere they can have a good feed and access to streams. The high pastures of the Pyrenees provide a welcome relief for them during the scorching months of July and August. They can sometimes be seen in some peculiar places, having a lie down in the grass on a steep mountain slope, or on a walkers’ trail. The transhumance is still very much alive here as the shepherds and their dogs drive the cattle up the livestock trails when the snows disappear and then back down again when the weather turns cold and the threat of snow returns.

Semi-wild horses can also be found here. Similar to the cattle, they graze on the high-mountain pasture and are taken up and down as the weather dictates. Visitors are more likely to see these horses in the Catalan Pyrenees, particularly in the mountains around Puigcerdà; as well as border areas in neighbouring Aragón, such as Astún ski resort.

And we should not forget the sheep and goats, which also climb high to reach abundant food supplies. They help to keep grass and undergrowth in trim, reducing the threat of wildfires.

Recent Comments